By: Branislav Cvetković, museum advisor

Once upon a time, travel was easier because there were no hard borders, border crossings, visa regimes and passports in the modern sense and the key reason besides trade was pilgrimage. Hajj are practiced in all religions so there are no big differences between them, as evidenced by the “Holy Road” between Athens and Eleusis, the oldest remnant of a pilgrimage in Antiquity, and network of roads “El Camino” in Western Europe leading to the Galician Compostela. This form of religious tourism was a lucrative business as it is today. The visit to the “holy places” was accompanied by special souvenirs in form of eulogies, reliquaries, phylacteries, brandea, myrrh flasks, badges and pectorals…

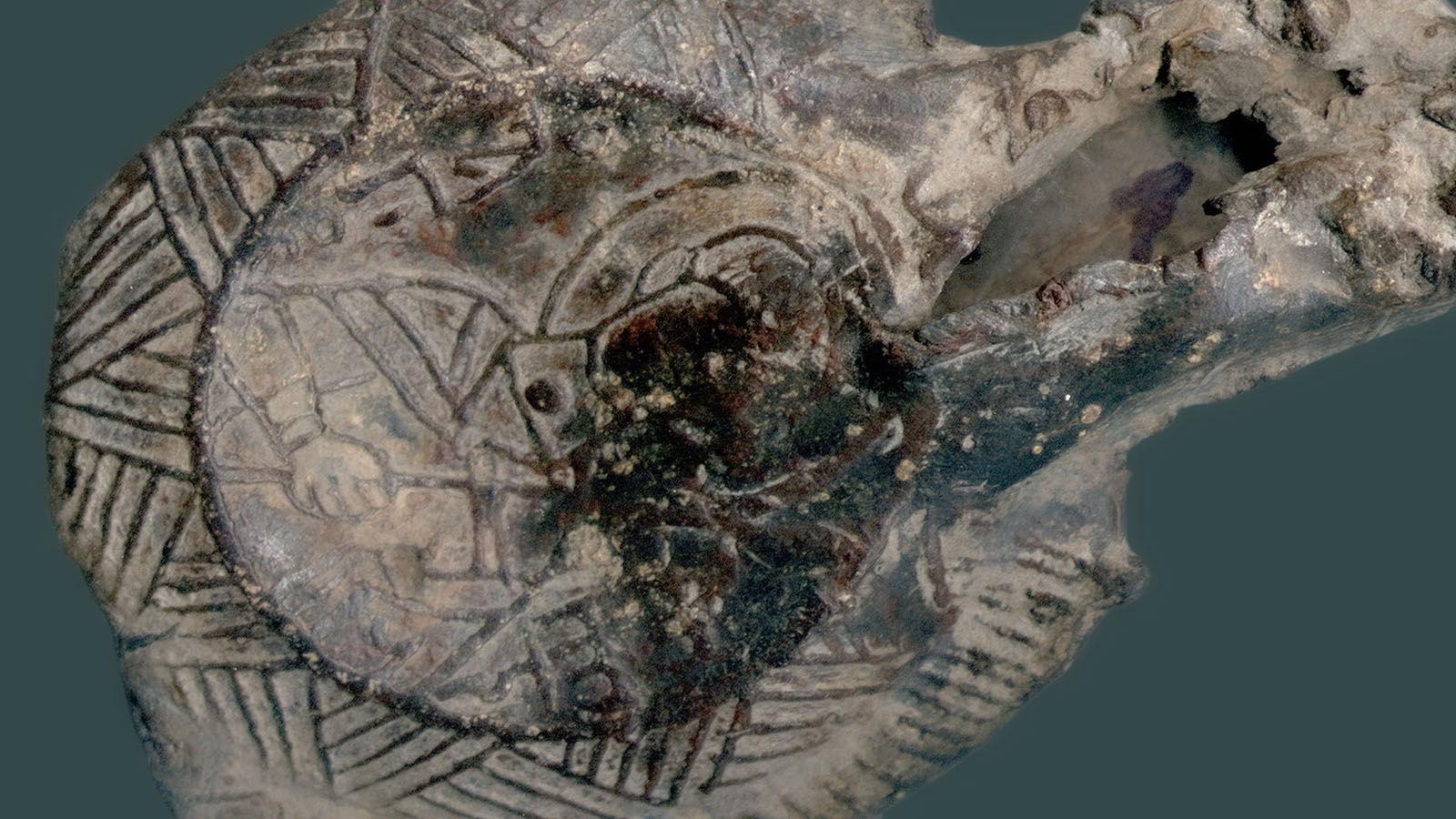

Our museum has a valuable specimen of this type, a late Byzantine lead flask (13th –15th C.), from the basilica of St Demetrius the Myroblytos, the most revered Christian cult site in Thessaloniki. It is an accidental find from the village of Belušić in 1993. It belonged either to a pilgrim who brought it from Thessaloniki or to a Greek who lost it in our region. There are a small number of similar flasks in our country, two are kept in the coffin of King Stefan Dečanski, a couple are from Mitrovica, one from the Stalać fortress is in the Kruševac museum and in addition to ours there is a fragmented specimen from archaeological excavations on Ras and one excavated in Studenica. Many more are kept in museum and private collections in Bulgaria, Greece and Russia, while in Western Europe there are only four known, two in the British Museum in London, one in the Louvre and one in Sassoferato, Italy. Our specimen, however, has no analogies because due to its special mold it is unique and therefore priceless.

Medieval flasks were small in size, always flat in shape with loops to be worn around the neck as shown in the 10th C. wall painting with figure of the hermit Aaron from the Nubian church in Faras. They often had representations in relief inscribed on both sides. They were made of ceramics, like the Egyptian ones from the sanctuary of St. Menas, and had frontal figures of the saint between two camels. Those from Holy Land were sometimes made of silver-plated alloys with multi-figure scenes in relief. In contrast to flasks from the 4th to 7th C., which therefore have scenes and figures rendered in a classicist manner, those from the late Middle Ages have crude and linear representations. Such are those from Thessaloniki which have a bust of St. Demetrius on one side and on the other a bust of other revered Thessalonican saints such as Theodora, David, Nestor or Lupus. These half-length depictions in medallions are framed by ribbon decorations as halos and mandorlas, signs of divine energy of the saints.

The flasks were actually recipients, they always contained a liquid from a “holy place”, consecrated water, oil, myrrh or, as in case of the Thessalonican flasks, lythron, a mixture of earth and blood of the Thessalonican saint who did not have real relics, but his burial place was worshiped as site of his martyrdom. Therefore, those flasks were not only souvenirs from a visit to Thessaloniki, but also amulets worn around the neck and on the chest. That the belief in their efficiency was widespread is confirmed by the fact that all known examples of flasks in museum collections were opened because their contents were used.